"Large numbers of illegally-employed construction workers are believed to be operating throughout the Baltic region, partly as a result of the movement of large numbers of indigenous workers to Western Europe where skilled builders, plumbers and electricians can command large salaries. Many of the illegal workers are believed to come from Ukraine, Belarus and Russia."

The proposals, we are informed, are to be included in an amendment to the Cabinet of Ministers’ regulations concerning "Labour Protection Requirements During the Performance of Construction Works". The Baltic Times notes that the Latvian government has yet to finalise these regulations, and it is to be hoped that they will have an 11th hour conversion and avoid taking the step of shooting themselves in the foot in this way. Latvia needs more migrant labour, and needs to make it easier (not more difficult) for migrant workers - at all levels - to enter the Latvian labour market.

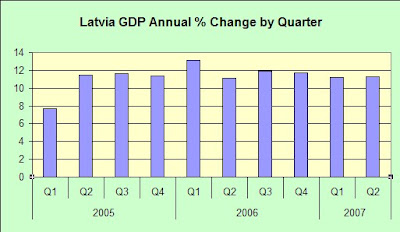

And here's why:

Is Inward Migration A Solution To Latvia's Labour Shortages?

As has been repeatedly argued on this blog, given that a strategy of relying exclusively on fiscal tightening and strong deflation to address Latvia's overheating problem is fraught with risk, and may even in the best of cases fail to deliver the results anticipated, another possibility which could be be put under serious consideration would be the application of a determined policy mix involving both decreasing the pace of the present economic expansion and increasing the economy's capacity for expansion by loosening labour market constraints somewhat via the use of an open-the-doors policy towards inward migration. This would involve the active promotion and encouragement of a flow of migrants from either elsewhere in Eastern Europe or from points further afield. Such a move would seem sensible, and even viable given the fact that Latvia is a pretty small country. However, as Claus Vistesen notes here, this can only be thought of as an interim measure, since, as the World Bank has recently argued, all the countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia are effectively condemned to face growing difficulties with labour supply between now and 2020 (so in this sense what is currently happening in the Baltics may be thought of as an extreme harbinger of the shape of things to come).

But given this proviso it is clear that a short-term inward migration policy may help Latvia escape from the vice within whose grip its immediate future seems condemned to lie. Such short term advantage may be important, since longer term solutions like increasing the human capital component in the economy and moving up to higher value activity, whilst important, need much more time to be able to have any noteable effect. You simply cannot take a 20 year old with a basic school leaving certificate and turn him or her into a high value technician overnight, and especially if you don't have that many twenty (or 15) year olds to play around with in the first place.

What is at issue here is transiting a fairly small economy from being locked onto an unsustainable path over onto a sustainable one.

As Claus notes in this post, Estonia has already taken some tentative steps in the direction of making access easier for external workers, and Estonian Economy Minister Juhan Parts is busy working on a set of proposals - which he is to put before the Estonian Parliament by November - which will attempt to address Estonia’s growing shortage of skilled workers. The quota of foreign workers will be doubled to about 1,300 and the bureaucratic paperwork is to be significantly reduced . Now it is true that Parts is still to bite the bullet of accepting the need for unskilled workers too, but in the present situation a start is a start.

Poland has recently being making more sustained efforts to attract workers from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, but also from more distant lands like India, while the Czech Republic, which has already decided to introduce a kind of green card system for workers from other East European countries has representatives out in Vietnam. In this sense if Eastern Europe is to overcome the looming crisis, then she must certainly be imaginative, and be prepared to offer incentives and advantages to migrants, and not only to skilled ones, since if you have only a few children what do you really want them to do, the most menial jobs?

The last IMF staff report(September 2006) already drew attention to the fact that a number of Latvian economic analysts had been calling for an expansion in inward migration in an attempt to alleviate shortages and to dampen wage pressures. However, it seems that local policymakers generally have been taking the view that this would only have the effect of replacing domestic low-cost workers with imported ones, thereby holding down wages and promoting further emigration. The problem is that if the current wage-cost driven inflation continues then a hard landing will become inevitable, and with a hard landing their will most probably be another exodus of people driven out in search of work, so this is really no solution.

The IMF was, in fact, cautiously positive on the need to open up the labour market:

The mission saw a role for targeted temporary immigration of high-skilled workers to relieve growth bottlenecks, and cautioned that Latvia’s current labor shortages may be short lived if growth were to slow at home or in those countries where Latvians are currently working. To boost domestic labor supply while moderating demand, the mission recommended easing the pace of economic growth, improving productivity in the public sector to free up labor, and further increasing labor force participation by raising the untaxed minimum under the PIT.

However being realistic, we need to note that Latvia certainly faces significant difficulties in introducing any kind of pro-migrant policy. One of these is evident, since any broad opening of the labour market may ultimately simply serve to put downward pressure on unskilled workers wages in a way which only sends even more of the scarce potential labour Latvia has out to Ireland or the UK or elsewhere. A recent report by the US Council of Economic Advisers made some of the issues involved relatively clear. The report cited research showing immigrants in the US on average have a “slightly positive” impact on economic growth and government finances, but at the same time conceded that unskilled immigrants might put downward pressure on the position of unskilled native workers. Now in the US cases these US workers are unlikely to emigrate, but in Latvia they may do.

Another difficulty which arises is the lack of availability of accurate data on the actual scale of either inward or outward migration in Latvia (this difficulty is noted by both the IMF staff team and the Economist Intelligence Unit).

As the IMF staff team note in IMF Selected Issues (2006) official statistics show that Latvia's population has declined markedly over the past 15 years, owing to both net outward migration and to a birthrate which has been well below reproduction rate since the early 1990s.

According to Latvian government data, Latvia had nearly 400,000 fewer residents in 2005 than it had in 1990. And according to the IMF calculations the population decrease is about equally explained by net outward migration (71 per 1,000) and by natural population decrease (births minus deaths, 75 per 1,000).

As the IMF comment:

"The fall in the population due to natural causes.......is also quite worrisome, as it continues unabated and will begin to exacerbate a shrinking labor market in a few years’ time."

According to the most recent estimate from the Bank of Latvia some 70,000 Latvians, or around 6% of the labour force, are currently working abroad - mostly in the UK and Ireland - but the true number is very likely considerably higher (IMF Selected Issues Latvia 2006, for example, put the figure at that point at nearer 100,000).

One of the difficulties that anyone trying to make an assessment of the labour shortage situation in Latvia faces is that official statistics measure only long-term migration, and, following the practices of Latvia’s Citizenship and Migration Board, long-term migration refers to "individuals who leave Latvia with the intent of settling in a new country for at least one year and who report this intention to an appropriate authority". As a consequence most of the data do not capture several important categories of migration:

a) illegal migrants who move permanently to another country without proper authorization from the receiving country,

b) permanent migrants to another EU country who do not report their change of residency, and

c) temporary migrants to another EU country who are not required to report their arrival in the receiving country.

The latter two categories would seem to be especially important in Latvia’s case, given that since EU accession, many Latvians have been moving to Ireland and the U.K. - either permanently or temporarily - to seek and obtain work.

On the other hand, if we look at the situation the other way round, in terms of arrivals in the UK or Ireland - as Latvian Abroad has in this post here (and this one) - then we may be better able to get a better idea of the numbers involved due to a difference in the quality of the statistics maintained. As Latvian Abroad points out, the numbers we actually find are somewhat below the normal headline-making level, but still substantial:

It's actually Lithuanians who have been the quickest to leave their country. 3.3% of Lithuania's population has ended up working in UK or Ireland. (Since UK only registers those foreigners who work there, the percentage of working-age Lithuanians who have left is probably 5-6%.) Latvia is second, with 2.5% of population gone. Slovakia is third and Poland is fourth. That surprised me a bit, because there are so many newspaper stories about Poles in UK and hardly any about Slovaks. Estonia is fifth. The emigration rates from Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovenia are much smaller.

As Latvian Abroad also notes the numbers leaving for the UK and Ireland have been dropping steadily since 2006 (although in the Irish case it is not clear to what extent the slowdown in the Irish economy, and in particular in its construction sector, is responsible for this, in any event the Irish data can be found here, and the UK data here).

Several recent surveys also suggest that the potential for outward migration remains substantial. For example, a survey conducted by SKDS (Public Opinion on Manpower Migration: Opinion Poll of Latvia’s Population) in January 2006 revealed that about 22 percent of Latvian residents see themselves as being either “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to go to another country for work “in the next two years”. Based on the current estimated population, this translates into between 350 and 450 thousand residents (between 15 and 20 percent of the 2005 population). The survey also indicated that these respondents were significantly skewed toward the relatively young (15-35), which would significantly reduce the working-age population and labor force in the near future. These respondents were also slightly more likely to be male, less educated, low-income, employed in the private sector, or non-Latvian.

But the biggest problem which arises in the context of projected in-migration as a partial solution to Latvia's present difficulties is a cultural one, and is associated with the historic legacy arising from years of unwilling participation in the old USSR, namely the presence in Latvia of large numbers of Russophone Latvian residents who are non-citizens. The scale of the situation can be seen from the table below.

(please click over image for better viewing)

Essentially out of a total Latvia population of 2,280,000, only 1,850,000 are Latvian (and hence EU) citizens. Of the remainder the majority (some 280,000) are Russians. And these Russians are not recent arrivals, but live in Latvia as part of a historic Russophone population which build up inside Latvia during the period that the country formed part of the Soviet Union.

In fact, if we look at the chart below, we will see that during 2003 the rate of out migration from Latvia seems to have increased substantially, as membership of the European Union loomed.

(please click over image for better viewing)

But what happened in 2003/4 wasn't simply an increase in the volume of migration, it was also a change in the direction of migration, away from the CIS and towards the EU. The majority of the pre 2004 out-migration was actually towards the CIS - official Latvian statistics suggest that over half of the Latvian residents who left Latvia between 1990 and 2005 emigrated to CIS countries - and it is reasonable to assume that many of these migrants came from the Russian speaking population.

So obviously any attempt to revert the flows will confront Latvians with some awkward and difficult cultural decisions, but then these are in-principle no more complex than those which would be posed by following the Polish example and attempting to establish a significant Indian community, or the Czech one and looking to bring in Vietnamese. As I say, Latvia is a small country, and the numbers involved are not necessarily huge, but perhaps the leap in the mindset which is required in fact is. As such the sustained exit of Russophones back into the CIS may only have served to delay, and make more difficult, a process of reconciliation which now, above all, has become economically expedient for everyone concerned.